Gerard Tsutakawa | Chasing Challenges

In this episode of Inspired Design, we head to the Wing Luke Museum for an exclusive guided tour of the Gerard Tsutakawa: Stories Shaped in Bronze exhibit with architect and exhibit curator, Rachael Kitagawa and exhibit developer, Blake Nakatsu. Then we have the privilege of chatting with the renowned sculptor himself at his family home and workshop in Seattle.

Listen on your platform of choice

[abcf-grid-gallery-custom-links id=”4804″]

Explore this Episode

Learn More

Wing Luke Museum – Gerard Tsutakawa

VISIT EXHIBIT

Gerard Tsutakawa: Stories Shaped in Bronze.

VALUES

People give us meaning and purpose. Relationships are our foundation. We desire community empowerment and ownership. To do this, we have found the following: The work is labor intensive. The work requires flexibility. We willingly relinquish control.

MISSION

Connect everyone to the dynamic history, cultures, and art of Asian Pacific Americans through vivid storytelling and inspiring experiences to advance racial and social equity.

Episode Transcript

Blake Nakatsu:

I think what the exhibit does is tells the story of Gerard and George and through the pieces, we can tell those stories of different periods throughout their careers. You can see different things that they’ve tried in the past. Lots of the stories of why we see the pieces out in public as they are.

Gina Colucci:

I’m Gina Colucci with the Seattle Design Center. Every week on Inspired Design, we sit down with an iconic creator in a space that inspires them. Today we are exploring the work of Gerry Tsutakawa first at the Wing Luke Museum, and then at his home workspace in Seattle. Most of you have seen a piece of Gerry’s work. Chances are, if you’ve ever been to a Mariners game, you’ve walked past, you’ve taken a selfie with, you’ve stood by The Mitt. The exhibit is so unique because you get to see George’s work and Gerry’s work side by side. And this is important because you can make the connections of them as father and son, but then you can also make the distinctions between them as individual artists. And George had such an influence on the artist that Gerry became. Seeing this exhibit really will shift your perspective of and give you the appreciation for what it takes to get one of their pieces through development, to a final product, and then installed in its home. Putting this exhibit together was no small feat.

Rachael Kitagawa:

My name is Rachael Kitagawa and I’m a local architect at Hoshide Wanzer Architects. And I’m the curator for this exhibit for the Wing Luke Museum. And I worked closely with Gerard Tsutakawa and Kenji Hoshide as the exhibit designer.

Gina Colucci:

Rachael explains to us why having their work side by side is so important.

Rachael Kitagawa:

Gerry Tsutakawa has been a friend of my family’s for a while. He actually went to school with my father-in-law and has known my husband for a very long time since they were small. And so, because we’ve known Gerry for so long, we’ve known his work and obviously the whole Seattle area knows his work. Gerry’s become sort of a Jack of all trades. He’s not just an artist. He can do it all.

Rachael Kitagawa:

In the exhibit, we highlight both Gerry and George, because George obviously had such influence on Gerry’s work. Gerry apprenticed for George. And obviously some of Gerry’s memories was sitting in the studio at the house and watching his dad work while Gerry carved things into wood. So from a very early age, he was influenced by and was watching his father.

Rachael Kitagawa:

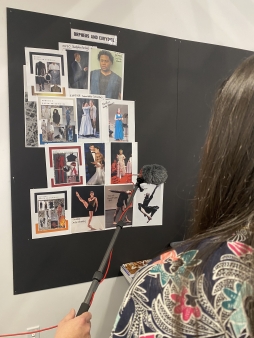

Their art has changed the urban fabric. It really transforms the spaces and the people who use it. A lot of George’s work is very peaceful and meditative with the fountains and the water flowing down, it really makes you stop and become aware of the whole area that you’re walking through and experiencing. Gerry’s work is very playful and whimsical, and it actually encourages you to interact with the pieces. You want to climb on it, you want to touch it. And he is also very conscious that people are going to interact with his pieces and he wants people to interact with it. One of the things we like to highlight in this exhibit is the making of the pieces and how Gerry and George thought about how these pieces are going to go together. How people are going to look at it, walk around it, interact with it, touch it, climb on it in Gerry’s case.

Rachael Kitagawa:

The other nice thing that we like to highlight in this exhibit as well is the community aspect of both George and Gerry’s work. They worked closely with a bunch of communities in order to develop the pieces and give an identity to some of these communities. We decided that because both George and Gerry’s work were so influential, embedded in the memories of a lot of people in interacting with spaces that we would take that direction to focus on how their work has positively influenced the community and how really great design can benefit everyone.

Gina Colucci:

What makes the experience unique is that you actually get to see some original pieces that were made for the exhibit, like the outline of The Mitt, which is unmistakable. It’s huge when you walk up to it.

Rachael Kitagawa:

This outline of The Mitt is a pattern. So you can imagine the outline shape of The Mitt. And of course the iconic circle inside The Mitt is painted a gold color and in The Mitt pattern is completely transparent. And so the way Gerry supported the piece as it is standing, he added struts, horizontal and vertical struts throughout so that you can read all the way through the piece. And also people standing behind the piece in order to take pictures.

Gina Colucci:

When we were at Gerry’s home and we were in his workshop in the back, on the ground you saw the spray paint outline of this, but here it looks so much bigger.

Rachael Kitagawa:

It does. When Gerry got the commission for The Mitt, he went to the interview with this very large, full-size cardboard cutout pattern for The Mitt. It was much too large for him to carry in, so he folded it up into three pieces and took it that way. We wanted to present that in the exhibit, but we realized that after how many years, it was very floppy and would fall apart and wouldn’t stand up, even if we hung it. So Gerry said that he would recreate a pattern of The Mitt. And so he bent the steel in order to make this pattern. And it’s encouraged that people can come and take pictures and selfies and submit it to the Wing Luke’s website so that we can collect some of these stories and pictures of people interacting with the exhibit, as well as his art. So if people…

Gina Colucci:

The exhibit shows the creative process of both George and Gerry. They make smaller models of each piece to work out the details.

Rachael Kitagawa:

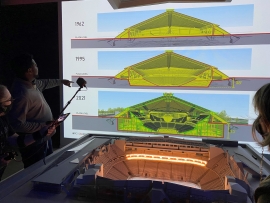

We are also highlighting a lot of George’s work in the exhibit. Over here you can see the maquette or working model to study the Seattle Public Library fountain called The Fountain of Wisdom. You can actually see the welds that were done in order to create those curvilinear forms. So if you look on the inside, you can see the circles that were needed in order to create those very organic forms that George is known for. A lot of these pieces, they’re not cast, they’re actually fabricated in sheets and formed into pieces. Sometimes when people see some of the fountains and sculptures, they think that it’s a cast bronze, but it’s actually not. He creates maquette, so small models, and takes those and studies them in multiple iterations until he finds one that he likes. And then what he does is he lofts it or creates patterns from those models at a full-size scale so that he can cut out the metal and form it up.

Gina Colucci:

Creating the sculptures is one part of the process, but then installing these works of art is a whole other feat.

Rachael Kitagawa:

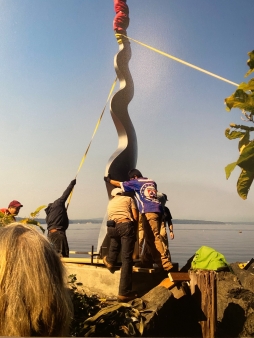

We have some collages on the wall about a few projects that he’s done such as the Illusion Dweller, the Kubota Garden projects, and the Maru piece. We talk about the Illusion Dweller as one of the highlights about some times the difficulties of installation of pieces. Illusion Dweller was cited on a very remote parks area out on a bluff near the water. It was down many rickety wood steps, and there was no way to bring concrete down in order to make the foundation of this piece. And so Gerry being the problem solver decided to bring a truck of concrete and buy a whole bunch of buckets and have a crew fill up these buckets of concrete, have them all cart it down these rickety stairs in order for them to create the foundation base of this piece.

Rachael Kitagawa:

And then they had to actually get the piece down. And so all these people that Gerry had gathered, as well as Gerry himself, his assistant, son, picked up this piece and carried it down these stairs. So if you come and see this, it’s really amazing. Some of these pictures of them hauling this piece down these very steep stairs and taking it out to this very remote location and lifting it into place with ropes and getting it installed. But it’s a very striking piece, especially if you’re on the water and you’re looking back and there’s this very bright, shiny metal sculpture juxtaposed against the very dark green foliage.

Gina Colucci:

The piece is quite tall. And then when you’re looking at these photos, you can see it’s not just four people, but it’s at least 10.

Rachael Kitagawa:

It’s a very fun piece to know the backstory about how it was put into place. And many of Gerry’s pieces take a bit of problem-solving about how to install it. The Tonbi, I believe a bunch of the streets downtown needed to be closed in order to bring in that very large fountain. And so it was done in the middle of the night, brought in and then installed in a night.

Gina Colucci:

We also got to see pieces that you don’t normally get to see in public. These are pieces that show how much of an innovator and problem solver Gerry is. These are pieces that show his ability to play and explore his creative side.

Rachael Kitagawa:

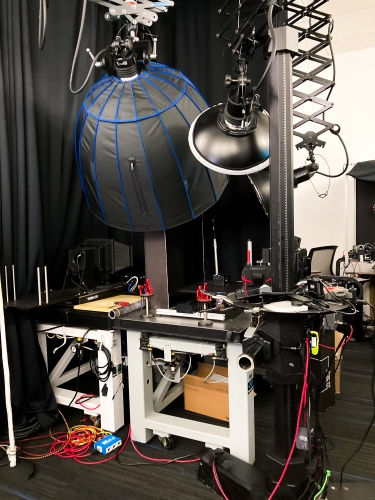

They’re concept pieces, is what Gerry likes to call it. And they’re fun ways to work out ideas. This one is called Liquid Lens. And so it’s a stainless steel box and it has a reflective lens on the bottom and water fills it so you’re supposed to look up and over inside the piece, and then you’ll see this reflection.

Blake Nakatsu:

Blake Nakatsu, Exhibit Developer for the Wing Luke Museum. If you’ve ever been in an indoor pool, the light that’s reflected from the water sort of creates this shimmering effect. If it were to move as I’m tapping the table that it’s sitting on right now, you could see that the water creates a shimmering effect from the box.

Gina Colucci:

At this point, we had seen so much. Rachael and Blake have such an interesting perspective on the exhibit because they created it. I wondered what were their favorite pieces in the exhibit?

Blake Nakatsu:

You’ll see in the back part of the gallery lots of maquettes. And my favorite is the smallest version of The Mitt. It’s the size of a half dollar coin.

Rachael Kitagawa:

A maquette is a small scale model so that a designer artist can study the different iterations of the design until they land on a specific design that they like. At least that’s how Gerry and George would do it.

Blake Nakatsu:

In these cases you’ll see lots of different maquettes by both George and Gerard and the mitts are right over here. The different renditions I think are awesome. You could see what potentially The Mitt could have looked like. The Mitt is so big and then you see the tiniest little mitt and it’s great.

Rachael Kitagawa:

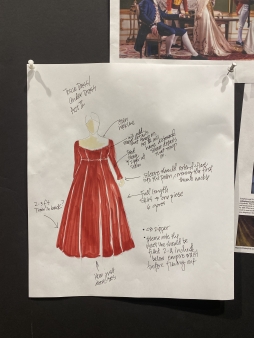

The pieces that I like in the exhibit talk about the actual fabrication of the pieces. So I love the Otamajakushi because it talks about how the pieces went together. But I also love this reproduction of some flat art that was at Gerry’s studio. It’s actually a section detail of the Fountain of Wisdom. If you don’t know what a section is, it’s like you took a piece and you sliced it in half so that you can see how it goes together. And it actually talks about the screws and the sizes of the pieces of metal and everything that goes into anchoring it into the ground. And in order to create that curve.

Gina Colucci:

Gerry is so thoughtful on every piece that he has made and is making. Seeing the details that go into the construction of each piece gave me such an appreciation for his art.

Rachael Kitagawa:

One of the amazing things that people don’t know about the inside of a lot of Gerry’s pieces is that they’re filled with sand and it acts as a heat sink so that people don’t scald themselves when they touch the pieces. Because if you go to other places that have bronze or metal sculptures, sometimes they’ll have little plaques that say, please don’t touch. It may scald or burn. Gerry was very sensitive to the fact that people are going to be interacting with these pieces. One of the first times he tried this technique was on Dragon, which is over in the CID Children’s Park.

Rachael Kitagawa:

He was commissioned to make this dragon for school-age children at the park. And at that time he also had a daughter that was school-age. So not only did he think of her and her friends as he was creating this piece, he had them try it out because he knew that they would be interacting with this metal piece. Sometimes it gets hot in Seattle as we’ve noticed this summer. He needed to figure out how the kids could play on it in all different types of weather. So he tried multiple different things to fill these pieces, but found that sand works the best.

Speaker 5:

Seattle Design Center is the premier marketplace for fine home furnishings, designer textiles, bespoke lighting, curated art, and custom kitchen and bath solutions. We are located in the heart of Georgetown, open to the public Monday through Friday with complimentary parking. Our showroom associates are industry experts known for their customer service. We are celebrating new showrooms and added onsite amenities. Visit Seattledesigncenter.com for more information about our showrooms and our Find a Designer program.

Gina Colucci:

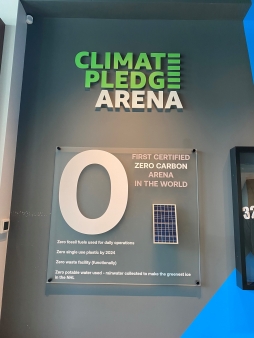

Decades later, Gerry is still designing his pieces to be interactive. We catch up with Gerry at his home workshop, as he’s creating the SeaWave for the Climate Pledge Arena.

Gerard Tsutakawa:

I designed this so that people can actually take a rest here or interact, or just going to be a photo op. This is hollow right now, it’s not quite finished. The bottom shape…

Gina Colucci:

You enter the garage and in the center is this giant sculpture, the SeaWave. At this point of its construction, it’s bright copper colored. And you can see the welds on each curve. It has different textures at this point because they’ve been sanding certain areas and it’s not smooth like it’s going to end up. And it’s in a very raw state.

Gerard Tsutakawa:

It’s probably 85% welded together. We still need to put one more piece on, but these are all weld seams, all these edges. And these are little fills to make the seams look better. And then you can see where it’s polished or ground out. And you were asking about tools. Mostly hand electric tools, but these birds are getting hand hammered. Nothing too fancy, that’s for sure. This is the sheet of bronze.

Gina Colucci:

This is the actual piece that will be at the arena or the Climate Change Arena.

Gerard Tsutakawa:

Yes. But you can see all these curves here. These are all hand formed. So you take a sheet of bronze and you make a pattern, you cut it out, and then you bend it over a pipe. We start with a pretty accurate cardboard pattern. But then transferring that to the bronze requires you to make all the little adjustments for radius. And a lot of these are twisted too. So you’re dealing with 1/8-inch bronze that you’re twisting and bending. If it was a bigger piece, would probably end up down at a machine shop and we’d use more power equipment, but this scale, it’s just buildable here.

Gina Colucci:

It’s really quite special, though, that this is kind of its birthplace and it’s going to be this new symbol.

Gerard Tsutakawa:

I think location is going to be very good. And everything at the Seattle Center gets a lot of heavy use and all that. So I think it’ll be fun to have it down there.

Gina Colucci:

Naturally, my next question was going to be, how was Gerry going to get the SeaWave sculpture from his garage to the Climate Pledge Arena?

Gerard Tsutakawa:

Well, I’ve built a lot of big sculptures here. We have a fairly good size door. It will be placed on a skid. We’ll drag it out the driveway, put some pipes on it and roll it onto my truck and drive it down there. That’s kind of the same process. If it gets bigger than this, then you need to hire a crane and a truck to get it down there.

Gina Colucci:

And as we’re talking, actually, I notice on the floor of the workshop here, you have a spray painted outline of the piece that’s at…

Gerard Tsutakawa:

At the baseball stadium.

Gina Colucci:

Yeah.

Gerard Tsutakawa:

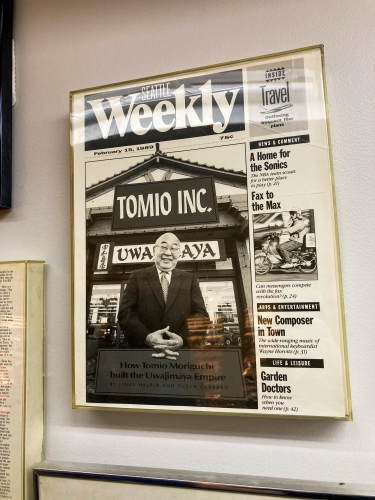

Well, when I was putting together the Wing Luke show, the curator asked me if we had a mitt pattern and I have the original mitt pattern from 1999, but it’s cardboard that’s nine feet tall and 12 feet wide. And she wanted to use it as an entry piece for the show. We pulled it out, we looked at it, I said it’s not going to last. It’s not going to hold up. So I said, oh, I’ll make a smaller version. And we built this out of steel square tubing. And actually, I’m really happy the way it turned out. The square tubing was hand bent here to form the curve. So first we made the pattern on the floor and then I stood here over the torch and a couple pipes and hand bent this thing. So you can see that’s fairly rigid and it has a lot of curves in it

Gina Colucci:

To get these tight curves out of this, I guess it’s thicker than my thumb, would you cut it into smaller pieces to get the curve? And that’s…

Gerard Tsutakawa:

I would take one radius and hand bend it on the table, but it didn’t want to bend. Square is a real difficult shape to reform. So I had to heat it up with the torch, sometimes getting it almost red hot and bending it. I had never done this before and I didn’t even know if we could do it, but I had two weeks left before the show opened. So I came on and started bending like crazy. And I think it turned out really nice.

Gina Colucci:

It’s amazing how you’ve been doing this your whole life and you’re still open to the idea of, let me just try it. Let me just-

Gerard Tsutakawa:

Challenges.

Gina Colucci:

What is [crosstalk 00:20:23]?

Gerard Tsutakawa:

I like the challenges of a new idea and concept. It keeps you going a little bit livelier.

Gina Colucci:

I wanted to know more about all of these tools within his workspace.

Gerard Tsutakawa:

We use hammers a lot. My father was a builder. He grew up in chisels and hand tools mostly. There was very few choices in power tools. He had a grinder and a cutter and a welding machine. So I was lucky. I got to inherit most of his hand tools, but of course nowadays it’s all cordless. That’s a nice one. We use this one a lot and I think it was a body and fender tool. A lot of times you want to tap something and you can’t get it in there. This one will make that shape.

Gina Colucci:

Is this a custom built, like a custom made?

Gerard Tsutakawa:

Yeah the handle was-

Gina Colucci:

OK, you can’t buy that at your store.

Gerard Tsutakawa:

We put the handle on because it broke. The handle came off so this was a free manufacturing of that.

Gina Colucci:

You can even see the wear and tear from the tape on it.

Gerard Tsutakawa:

Oh yeah. One of these days we should pull all the hammers out and take a picture.

Gina Colucci:

I don’t think I’ve ever seen so many different types. Even this mallet it’s like…

Gerard Tsutakawa:

Yeah. And surprisingly, we use all of these for different purposes. And these are called dollies and they’re for hammering against, hand forming. If you have a sheet of metal, you put a dolly behind it and hammer it from the front. And it helps create the shape by creating a little resistance or space behind it.

Gina Colucci:

Once we finished in Gerry’s workshop, we headed inside and sat down in his living room. You could feel the history, the walls were covered with his family’s art. It felt like an extension of the Wing Luke exhibit. This is Gerry’s childhood home. I got the sense like the past present and future were all joining forces within this home. I asked, all of your siblings ended up with career in the arts. Was that your parents’ influence?

Gerard Tsutakawa:

I have fond memories. My father was teaching watercolor at UW. On Saturdays he would bring his student works home and this living room would be full of student art paintings. And we’d be jumping over the paintings and he’d be grading them. And then we’d end up at the UW and running around the halls in the old art department. My mother and father were actually very social and they entertained a lot. So they’d invite other artists over for dinners and invariably by the end of dinner and after my mother cooked a Japanese meal and assuming painting would come out and the rice paper. And so they’d all sit around and do paintings. And so we were going, wow, that’s wonderful. But the next day you go to school and everything’s back to normal so we learned by observing a lot more than…

Gerard Tsutakawa:

My father didn’t really lecture or teach or encourage us to go into the arts, but because it was all around us, you learn that. All four of us kids had piano lessons at young age. And two brothers both went into music. My sister became a writer and she also curated shows and done a few books and all that, too. We all ended up in the arts of some sort. My father loved to go camping and he’s great outdoor enthusiast. So we’d go to the ocean and he’d paint and sketch and hike and all that. Go to Mount Rainier or went to Canada and a lot of different places.

Gina Colucci:

What’s something that you think about or would like to share with leaving a legacy or be able to tell future artists or future collectors?

Gerard Tsutakawa:

I probably like to be known as not just a designer, but a builder. My enjoyment is creating something new. It doesn’t have to be big. It doesn’t have to be fancy or small or whatever, but I just like the creative process. So I’ve been lucky enough that sculpture’s given me that opportunity to create things like that. I guess probably my idea of what I do, is a person that just enjoys building things.

Gina Colucci:

If an artist or a creator perhaps, or interior designer is at a roadblock, and they’re thinking, how do I keep going or be innovative? What’s some wisdom that you can…

Gerard Tsutakawa:

There’s so many talented young artists out there right now. And my advice is stay with a craft and keep working on it. It’s hard to pinpoint anything that’s going to influence somebody, but just stay with a craft that you’re in. And hopefully something good comes from it.

Gina Colucci:

A big thank you to Gerry for his candid conversation and letting us into his family home. And thank you to Rachael and Blake for the heartfelt tour of the Wing Luke Museum exhibit. If you’ve fallen in love with George and Gerry’s work like we have, there’s a walking tour you can take. Head to the Wing Luke Museum website for more information. Inspired Design is brought to you by the Seattle Design Center. The show is produced by Larj Media. You can find them at larjmedia.com. Special thanks to Michi Suzuki, Lisa Willis and Kimmy Design for bringing this podcast to life. For more, head to Seattledesigncenter.com, where you can subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media. Is there an iconic Northwest creator that you want to hear from? Head to our website and leave a comment.

Gina Colucci:

Next time on Inspired Design, we meet up with the Canlis brothers at their iconic restaurant.

Speaker 7:

We both love design. I think that’s fun. We both disagree all the time, which is fun. I was saying about the silverware, I knew I wanted that silverware-

Speaker 8:

Did you?

Speaker 7:

… 10 sets in. Yes.

Speaker 8:

10 sets in. It’s a team. We’re a team.

Speaker 7:

Yeah, we really are a team. I think because we agree on the really big picture stuff, then it’s fun and easy to fight about the small picture stuff, because it doesn’t matter.