Canlis | Kitchen Culture

In this episode of Inspired Design, we visit renowned fine dining restaurant Canlis. Owners, Mark and Brian Canlis along with Head Chef, Aisha Ibrahim candidly reveal their altruistic philosophies that keep this 70-year-old establishment at the forefront of the industry. Gain a newfound appreciation for their obsession to detail and the design secrets that lie around every corner.

Explore this Episode

Learn More

MAKE RESERVATION

VISION

Our vision for what it would look like if we carry out the mission perfectly: Canlis strives to be the best restaurant in America. Our people are growing emotionally, relationally, and professionally. We serve one another in a way that makes people feel valued and restored.

VALUES

We value trustworthiness, generosity, and other centeredness.

MISSION

To inspire all people to turn toward one another.

Episode Transcript

Mark Canlis:

This restaurant, at the end of the day, is really about being trusted. I think somebody comes in and says, “Man, tonight is a really big deal to me. It really matters. If I go there, it’s going to be okay. I’ll feel seen and known. I’ll feel served and cared for.” That’s what’s going on.

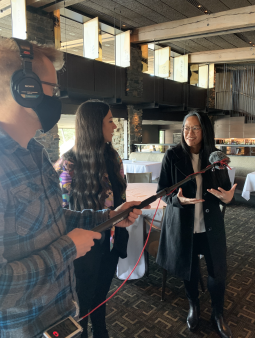

Gina Colucci:

I’m Gina Colucci with the Seattle Design Center. Every week on Inspired Design, we sit down with an iconic creator in a space that inspires them.

Gina Colucci:

On this episode of Inspired Design, we sit down with Mark and Brian Canlis at their iconic restaurant and chat with their new head chef, Aisha Ibrahim. Nestled on the hill of Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood, surrounded by trees, overlooking Lake Union, Canlis is the most respected fine dining establishment in the city. Founded 70 years ago by their grandfather, Peter Canlis, Mark and Brian proudly honor their grandfather’s legacy through their loving and attentive stewardship of the restaurant. They oversee everything, from daily operations, to architecture and design, to art procurement, even menu changes.

Brian Canlis:

My name is Brian Canlis. I’ve been here 16 years in my current role, which is the president, and I’m more of a day to day operations guy. I think Mark may be more of a big picture guy.

Mark Canlis:

I’m Mark Canlis. I’m his brother.

Brian Canlis:

You’re the CEO.

Mark Canlis:

I’m the CEO. Really?

Gina Colucci:

Mark and Brian honor their guests through every stage of their time at Canlis.

Brian Canlis:

It’s just like this subtle wink. It’s like the restaurant saw you.

Gina Colucci:

From the food…

Mark Canlis:

What does that look like on the fork?

Gina Colucci:

To the design…

Brian Canlis:

This was done as a tansu, as a super subtle nod to our Japanese heritage.

Gina Colucci:

To art…

Mark Canlis:

To make it pop at night, she put charcoal on it, so that’s actually charcoal on top of a photograph.

Gina Colucci:

Music and aromas…

Brian Canlis:

We think that smells delicious, but we think it can be better.

Gina Colucci:

They really attend to all five senses.

Mark Canlis:

Hundreds of hours just in designing the new shutter.

Brian Canlis:

Every single thing, we get super into.

Mark Canlis:

It’s us, roped into that tree, pruning the branches by hand. You want to know what it takes to run a restaurant? That’s how crazy the shit gets around here. And you might say that’s micromanaging, and sometimes it is, but also, that’s some of the joy. I’ve been looking at that tree my whole life. There’s a real joy to get to rope into it and just sort of manicure it.

Mark Canlis:

We need to do a 90-second Canlis architect and designer sort of run-down?

Gina Colucci:

Yeah, because let’s start from 1950.

Mark Canlis:

Can I just sort of humming, sort of a 90-second tune? I feel like we need a little song that comes in here, and then, doot-doot-doot. Okay, 1950.

Brian Canlis:

The original architect was Roland Terry.

Mark Canlis:

He’s kind of not a big deal yet. He’s a residential interior… he’s a residential architect.

Brian Canlis:

In partnership with Pete Wimberly. The two of them worked on the building, but Roland was the principle.

Mark Canlis:

Peter Canlis wants the restaurant to feel like a home. That’s a big deal.

Gina Colucci:

And Peter Canlis is your…?

Brian Canlis:

Our grandfather.

Mark Canlis:

At that point, restaurants were fancy, formal rooms with columns and mirrors, and they looked like Louis the XIV’s place, right?? We were taking all of our cues at this point in time, which would be the ’40s and ’50s, from Europe. So, the fact that Peter said, “What if you were as comfortable in a restaurant as you would be in your own home?” This is sort of me thinking a little bit. So Roland Terry comes in, and he’s the genius. He finds all these artists, like George Suyama, for example. Or, sorry, George Sugawa.

Brian Canlis:

He wasn’t born yet.

Mark Canlis:

Suyama will come later. And gets him to carve, like the very first sculpture he ever did is that door handle, right? Which is super cool.

Gina Colucci:

Yeah. Just, you walk in, and that is such an iconic piece. You recognize it right away.

Brian Canlis:

It’s his first ever commissioned sculpture, is our door handle. It’s pretty fun. But there are a lot of things that Roland did with Peter, like the kitchen was open to the dining room. That was something you never did in fine dining. The kitchen was where the servants worked.

Mark Canlis:

And the fireplace in the entryway. I’ve had people come in, sort of in their 80s and 90s and tell me, “I have never seen a fireplace in a restaurant before. We had no idea.” In fact, the woman who used to live on the property remembers it being built, and she was a little girl, putting her face up to the glass door and asking if they were building a home or a restaurant. It has a fireplace.

Brian Canlis:

Yeah, and there’s no front desk when you walk in. So traditionally in a restaurant, you walk in and you have a maître d’ and a desk, but you don’t have that for a while until you get into our restaurant. Eh wanted it to feel like you were coming over to his house.

Mark Canlis:

As you’re coming in.

Brian Canlis:

There’s furniture, and there’s a sofa.

Mark Canlis:

Like a human being.

Brian Canlis:

And Roland’s whole thing was blending the outside and the inside, so the stone outside carries through to the inside, and the beams carry through, and the glass carries through. So, that was fun. That was the ’50s.

Mark Canlis:

We remodeled the restaurant in the ’50s, in the ’60s.

Brian Canlis:

Yeah. Not the ’70s.

Mark Canlis:

Not really the ’70s. But in the ’80s, Jean Jongeward would arrive, for the great Canlis refresh.

Brian Canlis:

Yeah.

Mark Canlis:

And it’s worth saying, I think in those days, I think what Roland did, from just an exterior architectural design standpoint, I think that some of his genius was that he went so far beyond that. He knew artists, and he knew Irene McGowan, who came in and was doing all of this lighting work in ways that no one was doing at that time, and we still have a couple of her things. And so, it’s not really until the ’80s, I don’t know, maybe before, that it needs to be sort of refreshed in this way, and it gets super cool, right? She just…

Brian Canlis:

It was ’83 or so?

Mark Canlis:

Yeah.

Brian Canlis:

It was early ’80s. And then, about 15 years later, mid-late-’90s was Jim Cutler the architect redid it, and Doug Razor, the designer.

Mark Canlis:

So, Cutler wanted to work on a Roland Terry building, and just made it financially feasible for us in order for that to happen. It was like, “Hey, I think this is just such a cool project, and let’s try to go back to what maybe, had Canlis had a bigger budget in 1950, what would this have…” Because we were looking at original drawings, that kind of thing.

Brian Canlis:

Yeah, what were the things that Roland Terry couldn’t do because they ran out of money, and let’s do those things.

Gina Colucci:

And so, what were those?

Brian Canlis:

Oh, like bringing the stone columns, having more than two.

Mark Canlis:

Yeah, having the beams all the way through the space. Redoing the porte-cochère in the way that it was meant to be done. And it’s so different, like when you look at the way the restaurant was in those days. We look at old pictures. There’s zero HVAC on the roof. No air conditioning whatsoever.

Brian Canlis:

And no lights.

Mark Canlis:

There are no lights on the ceilings.

Brian Canlis:

So therefore, it’s only…

Mark Canlis:

There are only lights in the ceiling today. We just replaced one of those bulbs over the pandemic. Imagine none of those being there.

Brian Canlis:

So it was like candle light and ambient light, but nothing over the tables. So, it was dark and hot.

Gina Colucci:

Wow. And now there’s over 400.

Mark Canlis:

But I would say the guy who… It’s Doug Razor who comes in and I think sort of brings the restaurant, working off of what Jean did. They really changed it significantly in the ’90s, and that was so needed at that time, and he really guided us for the next 25 years.

Brian Canlis:

Yeah.

Mark Canlis:

Or more. We still… He’s technically retired. We still call him from time to time. And then you had George Suyama come in, from an architectural standpoint. So, I think the restaurant’s been so blessed. If you look at sort of who those… Those, to me, are so signature of the way that kind of northwest design feels.

Brian Canlis:

Right.

Mark Canlis:

And obviously, there’s so many other people who have built that sort of genre up, but I just feel like those are, we’re standing on the shoulders of giants in that sense. You know what I’m saying? It’s real.

Gina Colucci:

Because the business side of Canlis is so well done, it gives Mark and Brian the creative liberty to take risks, and to make sure every detail of the diner experience is perfect.

Mark Canlis:

The guest is in the spotlight. If we suddenly draw too much attention to something, then we are taking the guest out of the spotlight. That would be a bad design. Like, we have to remember, this is about them. So, all of this stuff is like, how are you honoring what they’re experiencing? This is too poppy. This is too flashy. But this suddenly becomes subtle. I want them to just not have anything jarringly take them out of that bubble, and I want it to slowly reveal itself.

Brian Canlis:

Just the butter knife that we have on our tables right now took us six months to achieve. We’re the only restaurant in America that has this butter knife.

Gina Colucci:

They spend hours procuring the place setting. If they change out the butter knife, it has this ripple effect.

Mark Canlis:

This is the butter knife.

Gina Colucci:

Here’s the butter knife. Okay.

Mark Canlis:

Okay, so the butter knife is a thing, you guys. We fell in love with the silverware, and we completely hated the butter knife. And then we just said to ourselves, wait, why does the butter knife have to be…

Brian Canlis:

It comes with the pattern.

Mark Canlis:

With the pattern, right? They’re their own thing.

Brian Canlis:

They’re their own course.

Mark Canlis:

It’s the only thing that lives on the table. It’s its own separate thing. So, we find this butter knife, we fall completely in love with it.

Brian Canlis:

They’re made in Japan. They’re gorgeous. They’re bronze. They’re sharp, which is the tradition in Japan. I had to convince this company to manufacture in Japan that we were worthy of the butter knife. I had to send photos. I had to send a description. I had to send them financial statements, that we were solvent. That took months and months and months, just for a single piece of cutlery. Now I have to convince Seattle not to steal them when they come in, so what we do is, we count them. Every time we clear, we count all the butter knives, and it’s already happening. People take them, and so we have a thing. What we do is, if there’s only three butter knives on a four top, then you say, “Oh, one must have fallen on the floor. I’m going to go drop these off on the kitchen. I’ll come back and look under your table.” And every time, the butter knife has found itself. “Oh, how fun, you found it for us.”

Gina Colucci:

They oversee design and production of locally made custom steak knives.

Mark Canlis:

The steak knife took three years for us to develop. It was like the steak knife was the joke of every team meeting, because we could not, could not figure out what a fine dining restaurant should do about a steak knife. Because knives that come in fancy silverware sets, they’re not really sharp enough, and they get their sharpness through serration, which is kind of a cheap way to do it. It’s like, I hear that on a table.

Mark Canlis:

And Rob Gray, this guy made these knives for us. He found this piece of Koa wood. And Koa has a lot of historical significance, so it’s just going back to the ’50s. We had a restaurant in Hawaii. Peter’s very first place in the late ’40s was in Hawaii, so a lot of our serviceware started in Koa. It started in this really beautiful Hawaiian wood. We still use it, but it’s very hard to get, and so we kind of, as a nod to that sort of historical thing.

Mark Canlis:

Now we don’t have to just use Koa, right? You have all sorts of cambia, bubinga…

Brian Canlis:

Lacewood, zebrawood, wenge.

Mark Canlis:

Sapele. Yeah.

Gina Colucci:

What do you think your grandfather would say?

Brian Canlis:

Oh, he’d probably think we’re nuts. I mean, even when we came back in 2003-’04-’05, the only plates were white and round and simple, and it made washing dishes, which is what our first job was, a little easier. But now everything is handwashed, and there’s 40 different plates out there.

Mark Canlis:

If you have 150, 200 guests, that’s 1,000 pieces of serviceware. If you’re handwashing, that’s a lot of handwashing.

Gina Colucci:

So, I’m holding both knives, the steak knife in my left and the butter knife in my right, from different parts of the world, from different creators, but there’s a very slight similarity, and they complement each other beautifully.

Mark Canlis:

So, the one in your left hand, the steak knife, we got to design from scratch. The one on your right, the Japanese butter knife, you can see that there’s little pins that are holding the handle to essentially the knife itself, that piece of metal that goes all the way through the handle, they match almost identically.

Brian Canlis:

And they get counted every single night and put in the safe and inventoried, because they’re a big deal.

Mark Canlis:

Yeah. Most restaurants might say, well, it doesn’t make sense. You can’t use home-grade stuff in a commercial setting. We would say, wait a minute, I think you can. I think you just have to be really intentional about how to do it. You can handwash things. You can be really intentional.

Gina Colucci:

This is what happens when you change the forks.

Mark Canlis:

You have to start looking at everything that the guest is experiencing in the restaurant. Does that make sense? So, these are the things you’re going to run into, and they’re all, they all need to speak the same language. It’s all a part of the story. It’s like a part of the way that something makes you feel. So then, when Chef says, “We need a tray for rice,” this is what happens. We’re adding this in. It’s like, we’re going to add a character into the movie. We’re like, whoa, okay.

Gina Colucci:

And then they’ll bring in a rice bowl that you can only find in Japan, so that the rice is served and displayed correctly.

Mark Canlis:

This is round three.

Brian Canlis:

Of these plates that we’re building.

Mark Canlis:

Of trying to understand.

Gina Colucci:

So, you build custom plates?

Mark Canlis:

Yeah.

Brian Canlis:

Oh, yeah.

Gina Colucci:

I don’t think people, everyone knows that, is that it’s mostly custom.

Gina Colucci:

Everything is there in front of you on purpose, for your experience.

Mark Canlis:

Because honestly, I think what’s special is, you get a bunch of normal people who decide for one night, they want to go out big. And when you come in, it’s probably not going to just be of happenstance, like oh, I just ended up at Canlis tonight. Whoa, how did this happen, right? It would probably be some intention around it. You would love it if it felt a little bit like the best meal of your life. You’re kind of wondering what the millionaires and the movie stars dine like, right? And this is what they have in their homes, so why wouldn’t we present that to you at Canlis? It just takes a little extra work.

Gina Colucci:

You think this process never ends. Is that…

Brian Canlis:

I hope not.

Mark Canlis:

I mean, this is the process of being considerate. I think that’s what fine dining is. It’s somebody saying, tonight, I’m going to consider, again, from scratch, what is the very best way to take care of you? What is the very most beautiful-est? Most beautiful-est thing I can put in front of you, right? What is beauty, or what is yummy, or what is kind?

Gina Colucci:

Yeah.

Mark Canlis:

If we’re not asking that question all the time, we’re getting stale.

Brian Canlis:

That’s what makes fine dining fun, because no other, there’s no ceiling. It never ends. You just keep pursuing a target that is always in front of you, of being the best, of being the most considerate, of being the most beautiful. There is no arrival.

Mark Canlis:

All of the stuff from a few years ago, we’d have been this excited about a few years ago, and now it’s like…

Brian Canlis:

Now we’re like, ugh, it’s so dated.

Mark Canlis:

Now we’re just like, I don’t want to look at that, right?

Gina Colucci:

So, would you say your innovation and desire to keep evolving is one of your key factors of staying relevant?

Brian Canlis:

Absolutely.

Mark Canlis:

I think it’s the thing that merits our being trusted. It’s a different dining scene right now. It’s post-COVID, or we’re trying to get to this post… We’re all different, and if we’re all different, guess what? Fine dining is all different, because this is a relationship between us and the guest, and if the guest is coming from a different place and feeling like they’re in a different sort of emotional space, or mentally, then we need to adjust to that. I don’t think we’re worth dining at if we’re not asking that question all the time.

Gina Colucci:

You keep evolving and changing. You are really rewriting the fabric of fine dining. You just hired a female head chef and a female head of your wine. What other things are you doing to change fine dining for the better, but also, what do you hope the future of fine dining looks like?

Brian Canlis:

the role that fine dining has always played in the larger restaurant community world wide is, it is the leader. It is the innovator. It is the tip of the spear. We are really excited about the tip of that spear right now being how you treat people, and how you care about the people that are delivering and making the food that you’re eating. That’s where all the innovation that we’re particularly inspired by, and that we want to lead, as this entire industry gets rebuilt, and we’re now being looked at more than ever as a worldwide leader in fine dining.

Mark Canlis:

There’s this really sneaky lie that is pervasive in business that sounds like, to be the very best, you have to use up your people. I don’t know how that snuck in. Obviously, there’s a lot of examples of it out there in the world. But there’s a lot of examples of the exact opposite, where it’s through your people, it’s through the glory of your people being fully alive and flourishing, that the company succeeds. That’s this restaurant’s story.

Mark Canlis:

And so, I think what we’re curious about is, how do we do that now? What does that look like now? If we’re becoming the kind of people we hope to become, and I’m not talking about accomplishing things, but like our character, what kind of dad, what kind of husband, what kind of leader, who am I in the community? What are those things you’re going to say at my funeral? Hopefully those are things that I’m proud of, and if not, that’s not me.

Mark Canlis:

I think as a company, what we want to do is say, okay, hold on, what’s on us? What is here that we control over? What are the privileges that we’re currently enjoying all the time, and which ways can we sort of choose to be thankful for those things, and then use those for good? And I think in business, it’s going to be all about the health of your team. And that is not pulling you from being successful. I actually think it’s pushing you towards that. Our hope is that if we could model what it looks like to turn towards one another in that way, then maybe that idea grows.

Brian Canlis:

When we brought in Aisha, we had mostly decided that she was the right chef for our restaurant before we had tasted any of her food. Her heart, and how she cares and thinks about people, and how she wants to lead, and how she wants to change the issues she’s wrestling with, like the way she was treated for 20 years in this industry, which is not awesome. She is so excited about being a leader that rewrites that story. That’s what got us excited. And then, oh, what do you know, she’s maybe the greatest chef we’ve ever tasted her food of. She can cook the lights out. And so, the combination of those two things, but the first one was more important. The food was a bonus.

Mark Canlis:

And we think that’s really different in kitchens. There are a lot of cooks who come through these doors and have never… they don’t get it. Like, what? Hold on a second. I thought this. And so, that’s our fault, our, the restaurant industry’s fault. We were the ones asleep at the wheel. We were the ones who were like, wait, how have we allowed our industry to become known for not caring for our own people? That is not okay.

Brian Canlis:

Part of that was also television, and the idolatry of angry chefs.

Mark Canlis:

This gets glorified in media all the time. Emotionally immature leadership that somehow we think is entertaining. God, that’s terrifying.

Brian Canlis:

It’s not a headline, like, “Executive chef was nice to cooks.” The stories that people gravitate towards are the negative ones. How do we create a positive story so exciting that that’s a headline? That’s fun for us.

Mark Canlis:

Aisha could be one of those ways. You’ve got to start putting leaders in the right places, so that they can influence people, and they can shine a different light into that world. So, we’re really excited. It’s so cool to have her here.

Gina Colucci:

Seattle Design Center is the premiere marketplace for fine home furnishings, designer textiles, bespoke lighting, curated art, and custom kitchen and bath solutions. We are located in the heart of Georgetown, open to the public Monday through Friday, with complementary parking. Our showroom associates are industry experts, known for their customer service. We’re celebrating new showrooms and added on amenities. Visit SeattleDesignCenter.com for more information about our showrooms and our Find A Designer program.

Gina Colucci:

We head into the kitchen to talk with Canlis head chef, Aisha Ibrahim. There are clocks everywhere, and different sections for every type of dish, and over the left is the main stove, and it’s a lot of stainless steel, and you have the warming station, and you have all the passes, which are large islands.

Aisha Ibrahim:

I wanted to redesign how we looked at stations and how we distributed certain dishes, and when you’re looking at efficiency of movement and how things hit the pass… This is a pass. This is a pass, and that is a pass.

Gina Colucci:

So, it’s like an island or a peninsula off of a stove, or…

Aisha Ibrahim:

Yes. Yeah, so the island is… The island in the middle of these kitchens, like when you look at a fine dining kitchen, there’s always the island. We call it the pass. That is the point in which we kind of pass off the food, and whoever’s expediting, it’s usually myself, and we have an expediter who works kind of in between dining room and front of… and the kitchen, and they sell the food. So, this is the area that we kind of get the final touches. We’re presenting the hottest plates. All the sous chefs are typically kind of standing around the passes, making sure that just before it leaves, we all have eyes on it, we’re all tasting everything.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Having greater access to hot ovens when you’re selling 75 of something a night, versus 40 of something a night, a lot of this movement makes a lot of efficiency. It’s all very deliberate as it’s moving out. So, everything needs to be moving in that direction. By that direction, I mean out of the kitchen.

Aisha Ibrahim:

When you’re cooking a piece of fish, we take it to about 75%. If that heat is where it should be, we use temperature probes and we’re testing it as it’s hitting the pass, the three-minute gap between here and going to the table, it’s residual cooking. So, by the time it hits the guest, it should be perfectly cooked. Then you’ve got a lot of moisture still, and you’re not losing moisture in that process. So, yeah.

Gina Colucci:

That’s fast, though. 3-4 minutes. It comes off. It gets here. You’ve got a food runner waiting.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Yes.

Gina Colucci:

And then it gets to the table, and if you’ve got like a four-top, you’ve got to time that perfectly.

Aisha Ibrahim:

It gives me anxiety thinking about it. Yes, that’s exactly four minutes.

Gina Colucci:

The kitchen is so in tune with the front of the house. Each dish and course is timed to the minute. Everything is paced around the diner’s experience. It’s even taken into account when a guest gets up from their table.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Actually, let’s back up. When you have your snacks, I get that table set ticket, and I determine how quickly you’re pacing yourselves throughout the night. Sometimes we have tables who just fly through their menus, and they’re out of savory courses in an hour. That means that they’ve hit first course, second course, third course, and they’re already into desserts after an hour. That’s pretty fast.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Todd, who’s our expo right now, will be like, “Hey Chef, these people, they flew through snacks.” And I’m like, “Okay, great. Oh, wait, let’s backpedal, because they just got wines.” So, when they get wines throughout the meal, then they slow down. The wine team comes in, and we want to give them that period of being able to present the wines, talk about it to the guests, and then get their wine glasses down, get the pour, get the spiel, give room for questions from the guests. So then, that kind of, we have to readjust our timeframes. So, I write bottle service or wine pairings, or whatever we have.

Aisha Ibrahim:

When a guest gets up to use the restroom, we have to really pump our brakes. We’re like, “Hey, hold on. Guest is up.” We’ll get a ticket that says guest up. That means that maybe you had gotten up to use the restaurant, take an important phone call, and they’ll let me know, like, “Hey Chef, it’s a phone call,” or “Hey Chef, they’re going to the restroom.” That means we slow things down. We don’t send the food out when the guest is up.

Aisha Ibrahim:

We try to think about how considerate we can be. So, when you’re going quickly, we want to move at the pace that you want to move in. Maybe you have a kid to go home to, or maybe you’re in a rush to get to a flight. We had a guest enter last week who had to be out of here in an hour to get on a flight, and we actually had to box up some petit fours for them.

Aisha Ibrahim:

It’s a lot of information moving at you at all times, but I think the thing that we try to strive for as a kitchen team, and kind of working with the dining room team, is how do we be the most considerate to our guests? If they’re eating slowly, let them eat slowly. If they’re eating quickly, let them eat quickly. If they have to get out of here in an hour, let’s see what we can do, you know? So, we don’t want to compromise the quality of the food. We don’t want them to get subpar food because they have to get out of here in an hour. So, we do everything we can.

Aisha Ibrahim:

It was funny to kind of plate something in a to-go container. You’re like, dropping technical things, and all of the sudden you’re adjusting it, and I’m like, so, am I 6:00? Which is what we call the guest’s perspective. It doesn’t really matter at that point, because the person will probably be eating this at the airport. But if they have to go, we want to send them with the hottest, most beautiful food we can.

Gina Colucci:

Aisha explains the board, and what her ticking process looks like.

Aisha Ibrahim:

So, the board has every single ticket, with all the dietaries. Maybe you’re sitting at seat two, you’re in seat one. It will tell us that on the ticket. We have all this information, so when we’re building your snacks, you shouldn’t feel anything if you’re a vegan. You shouldn’t feel anything if you’re gluten-free. If you’re coming in here and you’re dining, all these critical details, as long as I have the information at the board, and I’m able to convey that to the cooks, we design menus ahead of time to kind of be able to flex to that. No matter what these dietaries are, we try to be as friendly as we are.

Gina Colucci:

At this point, Mark comes into the kitchen and joins the conversation.

Mark Canlis:

I think we’ve had to be really intentional about saying out loud, are these people going to feel less than because of their choices, or because of a dietary restriction in that way? You go through great lengths to make sure that they don’t.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Yeah, I think it’s a part of being considerate to the guests. If someone is coming in here, they’re paying the same price as everyone else. They have maybe invested in a flight to get here. They have paid for a babysitter to come here. I think about my niece, who has every allergy. So sad. She’s a nut allergy, she’s allergic to so many things. And she’s half-Chinese, half-Filipino, and I’m like, you can’t eat nuts and shellfish? I’m so sorry for you. But I don’t want her to walk into a restaurant like this and have less than a good time, you know? I want her to have an amazing time.

Gina Colucci:

One thing that sticks out from all the chrome in the kitchen is this copper door, and it enters into this little room that you can actually see from the dining area, and inside is this wood fire stove, and it’s the original cooking area of the restaurant.

Aisha Ibrahim:

I dream of this being something that is kind of the center of the show, and right now, we’re still collecting information about what the Pacific Northwest holds. In my dream of dreams, in like the next season, instead of putting a protein cook out there, I wanted it to be our vegetable station. We celebrate meat so much in society, and in the ways that we eat in fine dining, but I think we cook so many vegetables here, and I think if we could utilize this hearth to kind of impart smoke, and really treat them as they should be. Treat them with as much care as a piece of beef, a piece of salmon, you know? So, if we could start doing that to vegetables, then we could really kind of… If the cooks can understand the importance, the food kind of starts to drive in the same direction, the guests will feel that. How we feel, I feel the guests feel. If we’re having a great night, I know the guests feel that. When we’re having kind of an off night, you can kind of feel it in the air, as well.

Mark Canlis:

Ostensibly, fine dining back in the ’40s and ’50s, you were just putting slabs of meat on the fire, right? It was not, I think, as holistic approach to food as it is today. So, the idea that you could take the original copper grill where we did all the steaks or lobsters or whatnot, and now be celebrating a piece of bok choy in the same way, I just think speaks to the progress that dining has made in this country, and our own understanding of food. So, it is one of the hardest stations to do, and historically, the chef ran that out there. I mean, that was there, essentially the pass that Aisha’s been talking about, used to happen all in that little room. And so, it’s just a special, albeit really, really, really hot room.

Gina Colucci:

Aisha’s path to becoming a chef was anything but straightforward. She discovered her passion for cooking while in college, laid up with a basketball injury.

Aisha Ibrahim:

In the process of getting back on the court, I was handed this cookbook in study hall one day, and I had zero interest in cooking. I never wanted to learn about cooking eggs, or eggplant omelets, or… I stayed out of the kitchen. I started to kind of read this cookbook. It was one of those Julia Child cookbooks, and my roommate laughs because I could barely cook eggs. She’s like, “I bet you can’t cook anything in this book.”

Aisha Ibrahim:

So, I started working my way through the book, and I would invite my teammates over, just because if someone tells me I can’t do something, it makes me just want to do it, and I’m like, “Okay, come over. I’m going to make salmon with asparagus tonight.” And everyone would laugh and not take me seriously, and I got so into it that by the time sophomore year was over with, I decided that I wasn’t going to go back to school. I wanted to enroll in culinary school.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Got home in the summer and said, “Hey, I’m not going back to school. I have enrolled in culinary school in San Francisco, and I’m moving to California.” I had never been to California before. Never picked up a professional knife before. Never been to San Francisco before. And just decided this was the time in my life to do that. So, I haven’t really looked back since.

Gina Colucci:

Do you miss basketball, or sports?

Aisha Ibrahim:

I do, but it was so natural to walk into a fine dining kitchen. They’re both, they involve a lot of athletic grace and movement, and you’re on your feet all day. It’s hyper-competitive. It’s a lot of muscle memory, how to sauce something, how to pick something up, how to cut fish, how to cut a piece of meat. Yeah, it is a lot of muscle memory, and it really requires, I think, a lot of patience with yourself, you know?

Aisha Ibrahim:

So, it’s fun to kind of run into other athletes on the line. You can always tell the way someone moves. Like, I worked next to a guy at a restaurant once who always opened the oven, and would drop down his right knee as if he was catching a grounder. So, after our third service, I was like, “Hey Justin, did you play baseball?” He was like, “Yeah, I played center field.” And I was like, “I knew it.”

Aisha Ibrahim:

So, yeah, to transition from that life into cooking, there were so many parallels. So, yes, I do miss sports, but I feel like this is an arena on its own, and it’s fun to play in there.

Gina Colucci:

You’ve cooked all over the globe, and in some well-known restaurants. What styles, techniques have you absorbed and kind of made your own?

Aisha Ibrahim:

Most definitely, Japanese, without a doubt. Japanese food, Japanese cooking, the culture of how product is seen through that perspective, and spending some time cooking there, I appreciated that. You know, I’m Asian. We don’t waste in our household. It was foreign to my parents to watch me make a chicken stock after going to French culinary school, and throwing away all these things. They were like, “What are you doing?” And my dad was like, “In France, that’s how it’s done. Not in this house.”

Aisha Ibrahim:

So, Japanese cooking and the way that we approach and care for product, the way that we care about where it’s coming from, and how to honor people who are bringing these products to our table. It’s part of our job to really honor the most respectful farmers and fishermen that we have. We try to support only local fish right now. We’ve got Taylor Shellfish. We have, we work with Northwest Bounty. We work with a lot of local fishermen who have just incredible access to byproducts like the cod. Have you had… the cod around here is incredible. It’s funny that we spend so much money importing Japanese cod. We’ve got gorgeous rock cod from the coastline that is just underutilized.

Aisha Ibrahim:

When it comes to Japanese cooking and techniques, smoking over hay, salt curing fish, learning how to age fish properly, that enhances the product even more. People think fish, and they think, oh, it’s fresh out of the water, and I’m like, no. Some of the best sushi restaurants in the world, it’s at least eight or nine days old, and it’s been handled with so much care.

Gina Colucci:

Sourcing locally, using almost, as much of something as possible is really important to you.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Yes, absolutely. I think the word sustainability, it has become sort of a joke. A lot of people like to use that word as if it’s a catchphrase, or you’re trying to win a reward or get a cookie for it, you know? We don’t want cookies. We want to actually cut down on food waste. Food waste contributes to so much of what’s warming up our earth, right? On top of that, this product that, as cooks, we can be a lot smarter in learning how to utilize.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Before we started sourcing this wheat straw, I thought, oh my god, we have to get rice straw from… Because rice straw imparts so much sweetness. It’s a very delicate style of smoke. That was going to be coming from California, and I’m like, no, wait, we work with a bread lab. They grow wheat. And the wheat straw, I started doing a lot of research about it, is very complex, is very delicate, it’s very sweet. We smoke fish with it. We smoke a lot of our vegetables with it.

Aisha Ibrahim:

We have a buckwheat sauce. I love this. So, we have a buckwheat sauce in one of our eggplant dishes right now, and the buckwheat is a regenerative crop from the bread lab. So, their planting season for wheat is gapped, and in those gapping seasons, they use buckwheat to kind of reintroduce nitrogen back into the soil. So, all that buckwheat comes, and we’re using some of that buckwheat. It’s our way to kind of utilize something that is not what they’re trying to plant, but they have to kind of plant, but it’s still a beautiful product. So, we’re using both the wheat straw and the buckwheat in the same dish, which is really fun.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Spain, I think, in terms of sustainability, Spain was huge in kind of really broadening my mindset, and working with a chef like Eneko in Spain, he’s an incredible leader in the kitchen. He works very closely with his people, and that’s honestly what drew me to work for him. When he offered me the job, I thought, that’s the kind of leader I want to be. Someone who is a family person, but also very grounded with their team, and is aware of what’s going on with their team. You don’t have to be an egomaniac to be successful. I think you can be just a very humble family person, and I really appreciate that about Eneko. He modeled that so well.

Aisha Ibrahim:

Gone are the days, I hope, that you’re just a body in a kitchen. We want to recognize everyone’s efforts, because we’re all here doing something that is special for the guests who are dining with us. So, it’s a huge platform to be the chef here, but I take it very seriously, and really want to work towards creating and continuing to create a kitchen that we can really see ourselves in, and identify with. Be opening the doors to more people who have been scared of fine dining for a long time.

Aisha Ibrahim:

I think we’re tying to figure out how to do this at the level we want to do it, and still maintain being a a reasonable human. I don’t want to detach from myself so much, but you have to put on a game face for sure, for service. But that game face shouldn’t affect how you treat others in the room.

Gina Colucci:

I wanted to know how Aisha’s Filipino heritage influences her cooking and the Canlis menu.

Aisha Ibrahim:

I immigrated to the US when I was six, but I grew up with my parents cooking for me and working. So, one of the dishes my mom always cooked for me was this eggplant omelet for breakfast, lunch or dinner, or to this day, I’m lucky, she makes it at the drop of a hat. The eggplant dish is a pretty humble dish that is found in a lot of Filipino households. It’s just a very strong, nostalgic memory, and something that is just so not fine dining in so many ways. We always think of fine dining as caviar and lobster and all this opulence, and I think the contrasting… Sometimes we do finish that dish with caviar for certain guests. We’re elevating something that might not feel special to the general public, but it’s something that I’m enjoying getting to introduce to people.

Aisha Ibrahim:

We burn the eggplant over the charcoal. We peel the skin, because it captures a lot of the smoke, and then we kind of just take eggs and whisk them. Unlike my mom, we use brown butter. So, we make brown butter, and we kind of let that eggplant hang out in the egg bath, and then we flip it back and forth and drop the whole thing into the pan, and it really gets foamy and nutty, and it’s typically eaten over rice, and I think the buckwheat is…

Aisha Ibrahim:

We make a buckwheat milk by toasting the buckwheat seeds and then seeping them and then pureeing that, and it kind of plays off of that kind of stickiness of rice the next day. So, if that’s what I’m having for breakfast, that smokiness comes from the very bottom of the rice pot, which is not something that we throw away. We actually fight over that in our house. But it’s that crispiness that is really nice. It’s a little smoky. The buckwheat is kind of a play on that. It hints on the process of what I’m thinking when I’m trying to introduce this to a dining room who has maybe never had it before.

Aisha Ibrahim:

It’s typically eaten with soy sauce, so we kind of glaze it with this beautiful tamari that we’re getting. We also finish it with a little bit of calamansi, which is basically like a key lime. It’s a very aromatic, kind of key lime play, that’s very commonly found in Filipino cuisine, but instead of that, we’re taking this Kyoto sweet miso. We finish it with apple cider vinegar, which is so common here. We’re in apple country. So, the acidity from the dish is brought into a more umami/acidic profile of this miso sauce.

Aisha Ibrahim:

I’m introducing flavors that I feel like are familiar to me, but so new to so many people, except once we had a Filipino order it as a first course and ask for rice. And I was like, so excited by that.

Aisha Ibrahim:

My mom grew up in the Philippines, and she would always go to the encyclopedia library that her parents had, and always pick up the W. And she’s like, “I don’t know why.” So, let me back up. Before I took this job, I was telling her about Canlis in Seattle, in Washington, and she told me this story. So, she would go to the encyclopedia and pick up the W, and always turn to the apples, and she would say aloud to her parents, or her friends, or whoever wanted to listen to her, that someday she was going to move to America and pick her own apples from Washington.

Aisha Ibrahim:

And so, she had never done that before. So, just before dinner, we invited her here early. My partner Sam, who’s our R and D chef, made her a spiced cider that we had just picked up from the market, and spiced with juniper berries that our forager brought us. So, it was really fun. We met her at the garden, had a basket, and she got to pick her Washington apples after all. So, it’s beautiful.

Gina Colucci:

We meet back up with Mark and Brian for a tour of the rest of the space.

Brian Canlis:

Let’s just walk, and then we’ll show you stuff.

Gina Colucci:

When you walk into the women’s bathroom, the first thing that you see is this giant window that looks into this small, open space outside, and in there are some plants and rocks, but the focal point is this giant trunk of a tree that extends so high you can’t see the top, and it’s been burned out on the inside, so it’s hollow.

Mark Canlis:

We do a lot of the foraging ourself, but there is a gentleman who helps us, and he discovered this burnt out cedar tree trunk way up high, like 7,000, 6,000 feet, and he has a license to kind of bring stuff down, and he said, “I found this years ago, and I’ve always wondered how to get it down.” Because it’s about 16 feet long. And we put it lengthwise.

Gina Colucci:

So, it’s here?

Mark Canlis:

Because there was a car accident.

Gina Colucci:

Oh, yeah.

Mark Canlis:

So, we had a car, a drunk driver, come off the freeway and hit the restaurant years ago, and it caught the restaurant on fire, and it burnt a tree right here, and we tried to save it. And so, we tried to save the tree, and then it died, and then we saved the trunk, and then slowly, the trunk sort of rotted away and the tree died. This garden has always been a really important piece of the ladies’ room. And so, when I found this cedar, I was like, oh my gosh, this is so symbolic of what we’re doing at the restaurant. I literally needed to replace a tree that died that’s been a part of our… So, there it is, right? And I just, I love it. I think it’s the most beautiful and stunning piece of art in the restaurant. I love it.

Brian Canlis:

But to get it… But there’s power lines right there, and so we had to hire a crane and an entire crew to lift this tree over the restaurant, and then thread the needle straight down.

Mark Canlis:

It took them days to get it out. So, this is off the top of the Cascades, right?

Brian Canlis:

Yeah.

Mark Canlis:

So, it was probably struck by lightning. It was burnt out. That’s why you see all the charred innards, and the outside, of course, the bark is peeled off, but you see the wood is unaffected. Cedar trees do this, actually. It’s a thing. And I love just sort of the death piece of it. I think so much of dining is the story of death to life. You are eating a plant or an animal, and it’s restoring and nourishing us, right? There was something about, I was like, “Yes, we need this.” And so, we bought it.

Mark Canlis:

This spot right here is one of my favorite design moments in the whole restaurant. It’s where all these materials come together, so you have this antique rug, you have the staircase, which is made of wenge. You have the bronze handrail, was designed by Suyama. You have the old Mt. Baker stone, which our grandfather put in. You’ve got this iron curtain, which was this artist named Dylan, who’s in south Seattle, who was inspired by Jean Jongeward’s curtain from the ’80s, doing a modern interpretation of it. And it’s all built into this Japanese stair tansu, which is about our Japanese history we have around here. And so, all of that comes together with the 1950 giant Guy Anderson, that’s actually from the ’70s.

Brian Canlis:

And if no one notices…

Mark Canlis:

That’s fine. Speaking of design, that was Don Clark that just walked past us.

Don Clark:

Are you embarrassing me?

Brian Canlis:

No!

Gina Colucci:

As we toured the space, of course we bumped into their artistic director, Don Clark, and we had the privilege of walking through his most recent project, which was a turkey illustration for their Thanksgiving menu, done in a mid-century modern style.

Brian Canlis:

How many restaurants have an art director? Like, we hired an artist to guide our art.

Mark Canlis:

So, I want to take you to another room. This room technically doesn’t exist.

Gina Colucci:

The place that doesn’t exist is a small, closet-sized room that doesn’t match anywhere else of the curated aesthetic of the restaurant. You enter through some beads, and there’s a small sofa and a chair, and then the walls are covered with memorabilia, and servers’ art, and they have old reservation books. It feels very welcoming and casual. It just felt like a secret hideout.

Mark Canlis:

We built this space for our staff. We recorded an album here with Sub Pop.

Brian Canlis:

Walt Wagner played on our floor for 20 years, and his retirement was a live album recording for Sub Pop of Walt playing Sub Pop hits.

Mark Canlis:

When he retired, we thought, well, hold on a second. Why not book in this? He’s such a legend. Why not just take the entire night and record? And Sub Pop was super into it. So, they came and set up all their fancy stuff, and made this album.

Mark Canlis:

Even the idea of a pianist, it might be considered old-fashioned, but I think if you take a man like Walt, who’s saying, I’m going to completely reconsider music. I might be in my 60s and 70s. He knows more about what’s on the radio today than any of us or our kids, right? And so, he’ll take these incredible songs and turn them into something on the piano, and to me, doing that with music is a part of the design of the guest experience, which is like, everything that you experience, taste, touch, smell, it matters.

Brian Canlis:

Yeah. People don’t expect to hear DJ Shadow when they come to the restaurant.

Mark Canlis:

No, that is an incredible one.

Brian Canlis:

This is DJ Shadow.

Gina Colucci:

And how old is he right now, playing?

Brian Canlis:

Oh, his 70s.

Gina Colucci:

He’s 70?

Brian Canlis:

Yeah. And he gets hit on more than any other guy in our restaurant.

Mark Canlis:

It’s really remarkable. It gives me such hope. I just, it’s something to aspire to. Like, when I’m in my 70s, I’m hoping, you know… Yeah, I don’t know how to say that.

Gina Colucci:

Just that passion, but also not being afraid of the new, right?

Brian Canlis:

Yes.

Mark Canlis:

Yeah. Yeah, why? Why are we afraid of it? Because it’s like we internalize that, and we say, maybe that’s a rejection of the self. Maybe that’s a rejection of where I came from, or what I used to believe. But think of how arrogant it would be to say that I have it all figured out. So, if we do that… Personally, those aren’t the kind of people we hang out with, and I think if you’re a company, that’s not the company that survives long term. You have to have the ability to say, we don’t have the answers. We maybe don’t know what the way is. We’re going to figure that out. And it means we’re going to have to change some things. We’re going to have to give up some of the sacred things that we used to believe in for something better tomorrow. So, cool, right?

Mark Canlis:

This is the fun part, when you’re talking about who are we as a company? What are we really doing here on the planet? How are we actually growing our team? Who are they becoming as people? That’s the work. It is a different kind of design work, but that’s the true work.

Gina Colucci:

Thank you, Mark, Brian and Aisha, for the candid tour of your historic and vibrant space, and sharing some of the Canlis magic with us.

Gina Colucci:

Inspired Design is brought to you by the Seattle Design Center. The show is produced by Larj Media. You can find them at L-A-R-J meedia.com. Special thanks to Michi Suzuki, Lisa Willis and Kimmy Design for bringing this podcast to life. For more, head to SeattleDesignCenter.com, where you can subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media.

Gina Colucci:

Is there an iconic Northwest creator that you want to hear from? Head to our website and leave a comment.

Gina Colucci:

Next time on Inspired Design, we meet up with Jean Thompson, owner and CEO of Seattle Chocolate, to tour the factory and learn more about her craft.

Jean Thompson:

It’s one of the oldest crops in the world. Like early, early on, the Aztecs and the Mayans used it as, that was the drink for the kings, and the peasants drank coffee. And they used the beans for trading. That was their currency. So, they’ve always, like historically, it’s gotten so much respect, and it wasn’t until it really, I think, got to the US and became kind of the candy, that it really didn’t get the respect that it deserves.