In this episode of Inspired Design, famed chef and restaurateur Tom Douglas gives us an in-depth tour around his eclectic home kitchen and yes, also his bathroom. We learn why it is essential to share your spirit when designing and how flow and function are a major priority for any kitchen.

[abcf-grid-gallery-custom-links id=”3861″]

Episode Transcript

Gina:

I’m Gina Colucci, with the Seattle Design Center. Every week on Inspired Design, we sit down with an iconic creator in a space that inspires them.

Tom:

Somebody walks into your restaurant, you want to share who you are with them and what your idea behind the restaurant was, pretty quickly.

Gina:

You can’t talk about Seattle’s food scene without mentioning Tom Douglas. Tom has been making food in Seattle for 35 years. He opened his first restaurant, Dahlia Lounge in 1989. From there, he launched more than a dozen other enterprises and has received three James Beard Awards, including Outstanding Restauranteur in 2012. His imprint on the city and the entire Pacific Northwest is unmistakable. He helped put Seattle on the map as a food destination. I got the chance to catch up with Tom in his home kitchen, where his mark on the space is immediately recognizable.

Speaker 3:

Hello.

Speaker4:

Can we come in?

Tom:

No.

Gina:

We meet his business partner and wife Jackie, and learn how they built their kitchen from the ground up.

Speaker4:

Thank you for having us.

Speaker 3:

Yeah

Tom:

Pleasure.

Speaker4:

Inviting us in.

Tom:

When we first moved into this house about 22 years ago now, [crosstalk 00:01:17] maybe 23, 24. Well, the first day we walked in, the mountains were crystal clear out in the mountains[crosstalk 00:01:24]November. Now you can only see half of them, but it always reminds me of that day we walked in here [crosstalk 00:01:31]and then we couldn’t afford the house. We did it anyway.

Speaker4:

Do you want to give us like a little verbal tour?

Tom:

I guess the question is there’s design; there’s function; there’s flow, and so when I go through it, I guess I speak to that because in the restaurant business, on the hotline, it’s all about fluff, right? And design is a little bit different. Because design, like you have to decide, do you want to commercial looking kitchen? Do you want a home-style kitchen? I kind of went both ways with that, but flow is number one. It’s like when you’re standing at the stove and you need hot water, or you need something from the fridge or you need to get to your cutting board, how does that work? How does that feel? And are you running back and forth through your kitchen or is everything just at your fingertips?

Tom:

And then the restaurants, each station is set up for a flow for that station and for what dishes come off of that station. So it’s kind of set up so that it’s at your fingertips, everything right there. And then in the restaurant, like you see my stack of saute pans, things like that.

Speaker4:

Yes.

Tom:

A pan like this, I just said a 12 inch saute pan or 10 inch saute pan. I might use this three times a week at home. I’ll use this 300 times a night at the restaurant. And so it’s just a different thing, and I have high expectations and I still have some of my original pans, 25 years later at Palace Kitchen of this All-Clad nice heavy pan. So some people might consider that design, because it’s a fancy looking pan. But to me it’s useful.

Speaker4:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Tom:

How does it function? So form and flow and function are huge issues in my kitchen.

Gina:

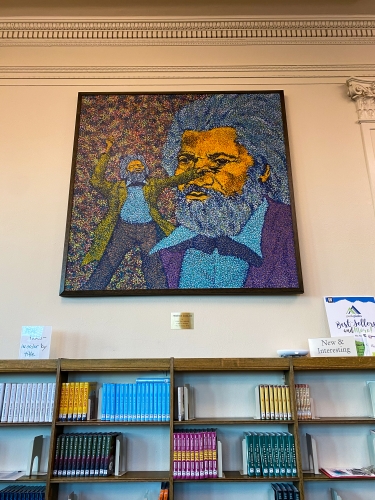

When you walk into their house, you’re immediately struck by the amazing view of the Olympic mountains. And then as you turn the corner, you’re in the kitchen and this kitchen is exactly what a professional chef would want. It is dialed in. It’s not a minimalist kitchen. We’ll put it that way. His kitchen is filled with everything that he loves, and there’s very little counter space left, but everything has a purpose.

Tom:

You can see everything’s kind of out and about. You might see in a restaurant, pan racks. My knives are all lined up ready for me to grab. Everything’s kind of out and about, but at the same time, I got nice wood shelves and hold up all my cutting boards and my big pots in the lids and things that you would never see in a restaurant. So that’s kind of a baseline of what I tried to do.

Speaker4:

You mentioned you bought this on 25 years ago.

Tom:

Yeah.

Speaker4:

Is this what the kitchen looked like?

Tom:

Are you kidding me? Your back is to the kitchen right now when we bought it. If you turn around, there was a shelving unit that came off the fireplace here. And so the stove was right there and the refrigerator was over here. It only had a four seat dining room. And so we just need more, we entertain a lot. And so we needed more space. So we took the kitchen and dining room, combine those, then took the TV room and made a kitchen out of it.

Tom:

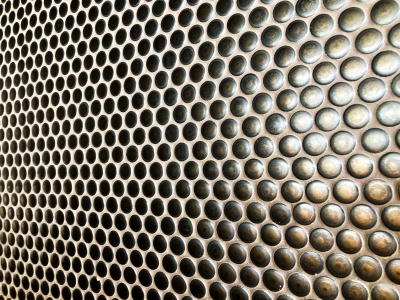

And then this over here, now that’s commercial. If you look in here, I have a two minute cycle dishwasher. So every two minutes it goes through a whole load. And then I have a spray nozzle that you see in every restaurant kitchen. But I have it tucked away because I’m entertaining over in my dining room, and I didn’t want to see that in my kitchen. So I have this tucked around the corner and there’s a big enough place to drop all the dirty dishes. So you don’t have to do it till later, but that’s what that is.

Speaker4:

That looks really convenient.

Tom:

Yeah. And when you entertain a lot, it is convenient. I can tell you, I can do dishes for a party of 30 in an hour.

Speaker4:

Well, then no wonder you entertain.

Speaker 3:

Yeah.

Speaker4:

That’s the best biggest way. And I want a little bit more insight on this island because walking into what used to be your TV room is now your wonderful kitchen. This island here is a very substantial part of it.

Tom:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Speaker4:

And so what was the reasoning and the shape?

Tom:

It looks like a baseball diamond. Honestly, if you look at interior of a baseball diamond, that’s what it kind of looks like, but it’s actually very functional.

Gina:

The kitchen Island is on wheels and you can push it to the corner of the kitchen, which shakes this professional prep kitchen and turns it into an amazing entertainment space.

Tom:

Around the island. I have large drawers. Each drawer is kind of dedicated to an area of service. So I have a whole baking drawer there. I have a pasta and starch drawer over there. On this side I have all my bowls in the bottom one and all my stuff like saran, rapid gloves and stuff like that in another. The top was intended that at the time when we built it, we didn’t have Hot Stove Society or cooking school. And we would often new classes and donate classes. And so I made it so that I could get nine people around this island, and I was the 10th, so groups of 10 we could do a cooking class together.

Tom:

And then we put it on wheels, which is unlike most islands. And if you look at the shape of the island, it fits right back into the corner there. So that when I have a party, I will put all the buffet out here, shove the island, then back when I’m done cooking and the lights go right over top of the buffet then. And so it’s well lit and it opens up this room for more traffic.

Tom:

And of course you can see the big hole in the island too. That was featured on the Oprah Winfrey Show. But yeah, that’s just a simple little garbage.

Speaker4:

Well, yeah. I was like, there’s a hole on it. Did you know that? And so speaking, I mean, you’ve mentioned that you have parties and you entertain. Is that a source of inspiration for you?

Tom:

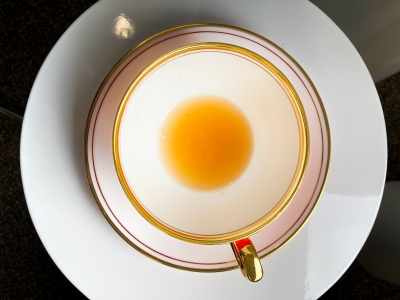

Perspective, absolutely. There’s a couple of things that go on there. One is I had 15 restaurants, right? And so I’m always thinking about new menu items, this and that. Maybe a new restaurant, this and that. So I keep a set of china from each restaurant here. And so if you look on this wall over here, I have maybe a dozen sets of china over here and I have more in the garage so that when I played something that I’m dreaming up for Lola, I can put it on a style of plate that matches Lola’s food and thought process.

Tom:

And that’s kind of why I do that. Plus there’s just fun to have. And then on the platter side down there, I have a whole collection of platters and I try to buy one, when we travel around the world, we try to buy a platter from each place as a memento so that when we’re passing around the table, it’s a conversation piece.

Speaker4:

Oh, shot glass.

Tom:

Exactly.

Speaker4:

So, I mean, going back to the different plates, would you say that each one of your restaurants obviously has its own personality? Is that part of your creative process? Do you kind of think of your restaurants as maybe people.

Tom:

Not necessarily people, but individual places, yes. I sure do. And they end up taking on my personality, Jackie’s personality. They end up sometimes if a chef has been there long enough, they’ll take on the management personality, especially in the service side of things. And it’s a gentle way to share your spirit, right? When you think about it, it’s like when somebody walks into your restaurant, you want to share who you are with them and what your idea behind the restaurant was pretty quickly.

Tom:

You don’t want it to be something that they have to come back six times for it. You want to kind of show that right away. And that comes across in the light fixture that you choose and the color of paint that you choose. And it comes across in your access to visual with the kitchen, like serious pie. I always wanted everyone to be able to see the wood fire in the oven. When I set up the dining room, I kind of worked it so that every table could see the wood fire. And so that was an energy that I wanted to bring to that customer. And just an immediate, oh my God, that looks delicious, or fire, people love fire.

Speaker4:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Tom:

Some people love it a little too much. They’re called pyromaniacs.

Speaker4:

Don’t we all? I know a few of them were past child. What would you say or which restaurant hits closest to your own personality?

Tom:

I don’t really think about it. Probably this kitchen does more than any of the in particular restaurants, I would say, because of the functionality of restaurants like Dahlia Lounge has 170 seats. You can’t get anywhere close to what you might do here, because you have to service a lot of people all the time, three meals a day, seven days a week.

Tom:

From the menu was probably more close to what I would relate to than the restaurant itself. And I would say that all of them are a moment in my time at Palace Kitchen, probably the closest if I’m in another city and I’m going out for one or two meals and I’m in a hotel, or on business, and I want a sense of place. I look for a place that has windows. I hate places that have no visuals to the outside world that you don’t know if you’re in Seattle or Paris. I hate that. So I looked for a place that has windows, activity and gives me a sense that if I’m in Seattle for two nights, that I’ve been there; that I didn’t miss a thing.

Speaker4:

So I want to touch back too on, you said, the menu is kind of closer personally to you,

Tom:

To my personality.

Speaker4:

Yeah, to your personality. Can you walk us through what it’s like for you to create a menu through that process?

Tom:

Yeah. You never know Where it’s going to come from. That’s so funny. We’ll take Lola for example, Jackie’s grandfather immigrated from Greece when he was 17, married a woman from Kentucky in Eastern Washington when he was working on the railroad and never had a chance to go back. She wasn’t interested and he just never had a chance. And one time when we were at Dahlia, I don’t remember why it happened, but we did a Grandpa Louie’s Greek vacation, dream Greek vacation plate. And it was just I did some Greek things, because I was in the mood for that or whatever. And so out of that came my book Tom’s Big Dinners. And so we took that one step further and made it like a five course meal out of that. And out of that big dinners came Lola, the restaurant, because we love that chapter, and we love the energy of that chapter. And we loved that she’s part Greek, and that word has a story all of our restaurants, so need to have a story behind them why they’re there. So I love that about it.

Speaker4:

Did you get to meet him?

Tom:

I never did meet Louie. No, never did. Jackie just was so embarrassed by me that she never took me over to him. Was Louie even alive when we met?

Jackie:

He was long passed.

Tom:

He was dead. Louie is dead to me. [crosstalk 00:12:55]

Gina:

One thing that surprised me, Tom is quite the collector. And we got a tour of his favorite treasures sprinkled throughout the kitchen.

Speaker4:

Little bus or what would you call them? Faces?

Tom:

I think they are. I have a $5 dough right here. The jar spice rub with love spice rub, if you can tell me what they are.

Speaker4:

Well, they all have a hole in their mouth.

Tom:

Yes, that’s true. Those are butcher string holders.

Speaker4:

I would not have guessed that. [crosstalk 00:13:23]

Tom:

I know you wouldn’t. So if you look at them in the back, they’re hollow and a ball of butcher twine fits in there, and you hang this in your kitchen and the twine comes out, so when you need to put your string, you just pull on it. I collect now post-World War II, Chakra Wear, vintage.

Gina:

Chakra Wear got it started in the 1800s, as a cheaper and more accessible alternative to ceramics coming from Europe and China by boat. The pieces were made from plaster of Paris and then hand painted. Chakra Wear surged in popularity after world war II. There were fewer ceramics coming from Europe, which was ravaged by the war and slowly rebuilding. Chakra Wear from this time period is known for its kitschy patterns and outrageous colors. By the 1960s, it had fallen out of favor as more durable ceramics became affordable in the US.

Tom:

I collect them. These are little wine stoppers of the same kind of vintage. And what’s cool about them, there’s only eight in the series, but because they’re hand painted, every one is different. So here’s four guys of the same series, but each one is a little bit different. And so I just always kind of thought they were fun.

Speaker 3:

Little bottle stoppers.

Tom:

Yeah. Bottle stoppers.

Speaker4:

What about the post World War II time period speaks to you?

Tom:

Well, it wasn’t so much the date specifically. It was more the energy of the items. And at that time I was a big E-bay guy and I was finding little bits and[inaudible 00:15:04] that I kind of enjoyed looking at. And I thought made a good collection, so that’s how that happened. I mean, if you look in my bathroom, I have a collection of shadow boxes or tribute boxes from a guy. He made them in his garage and in the Carolinas and his name is Jim Charles. And I got one, I saw it on eBay and I got one, I got to here. It was $20. And it’s like, this is goofy, but I kind of like it.

Tom:

I liked that American folk art kind of genre and not just American, but folk art. And I got it here and I fell in love with it. And now I have 50 of them and he just stopped posting, and I don’t know how to get any more. I don’t even know how to contact the guy. So it was kind of sad in a way.

Speaker4:

Yeah.

Tom:

Let’s go take a look at him for a second.

Gina:

Next thing I knew I was standing in Tom Douglas’s bathroom.

Tom:

Each one has got its own little story. So here’s James Brown, Say It Loud Soul, and then he puts a little story on the back and signs it. And that’s what they’re, and they’re $20. And they’re like the sweetest little deals. And so this is post World War II chocolate, that’s the kind of thing you would get at a carnival. It’s a King Kong statue. And I put a bunch of Jim beam bottle space needles around it, and I have to make a pedestal for him, but I have little Washington knickknacks and stuff like these as all, but I love these, these speak to me.

Speaker4:

Oh yeah. You got Michelle.

Tom:

Michelle and Barack and Jackie Robinson. And like I said down at canteen Alania and they’re kind of the decor on my back bar. Even stuff like this guy right here. That is a Tim Wolf. My guess is it came out of a pub in England somewhere. And it’s just been hammered around a piece of plywood and it’s just spectacular. And when you stand there to pee, you got to have some serious need to pee, because that guy stares at you right in the face.

Gina:

The tour continued back in the kitchen.

Speaker4:

You put so much of your collectibles into your restaurants.

Tom:

Not just into them, but the restaurants really are heavy with them. But I think, I did this over the holidays at hostels, show people how to take that very same butcher twine holder and put it on your cheeseboard. And kind of decorate around it. And when you have people over, there’s something to talk about. It’s like, it just is part of who I am. And so now we can have that conversation and I like taking your own individual designed pieces and having that conversation with people.

Speaker 3:

That’s amazing.

Tom:

Like this guy right here, the weenie man [inaudible 00:18:01] it’s like the goofiest thing you ever saw? It’s a framed paper marionette of a man holding a tray of weenies sausages. And why is that here? I don’t know. [inaudible 00:18:16] Exactly. It’s the same goofy little stuff.

Speaker4:

And what about these? Are they soap?

Tom:

These are sardine tins. And I like the boxes more than I did the sardines. So I kept the boxes, but I just found them in a grocery store. They’re still out there, out and about. And they’re really nice artwork. Martha Stewart loved these. She called me and asked me where I got those. I said, “Martha, I made them”. Just tins, and I put a washer on the back. That was magnetic. And so that it goes to my knife bar.

Gina:

This got lost in the conversation, but now he uses the tins to hold all his spices.

Speaker4:

What’s your favorite spice?

Tom:

Oh, posh. Oh my God. That was funny stuff.

Jackie:

It was a spice girlfriend back in the day. Oh yeah.

Tom:

Yeah. I started these, I think it’s just a beautiful fragrance and little goes a long way from a spice perspective.

Speaker4:

Does it remind you of anything?

Tom:

There was a restaurant in San Francisco called China Moon and Barbara Tropp was the owner. She’s long gone, but it reminds me of walking in there and walking into an old grocery the Viet Wawa in our international district or [inaudible 00:19:36] grocery, which was the first Asian grocery I used to shop at. And Stan was the owner there, and just had one of those long black hairs hanging out of his chin. And he was just the coolest guy and the Wing Luke Museum is where that is now. But yeah, I just love the smell of those stores and they all were fragrant [inaudible 00:19:56].

Gina:

We were coming to the end of our time together, and I wanted to know more about the inspiration and design behind some of Tom’s other iconic restaurants.

Speaker4:

Where do you begin when we touched on your process how you found a Lola, but when you decide you get that spark of I’m ready to open another restaurant, where do you usually find that inspiration?

Tom:

Well, Jackie and I design them and then we just kind of build off. I think the Carlisle room is a good example. I had one piece of folk art that I had. It’s a Bob Dylan. It was 12 feet wide and about almost 10 feet tall. And I saw it at a curiosity shop and I really spoke to me and I liked it. And so we designed the Carlile room, literally around that piece of folk art. It turns out we found on the back of it, it was part of the 1972 Grammy set. And so apparently there are four matching pieces to it somewhere they’re probably all gone, it’s my guess. It’s just on plywood and it’s just done with a brush and a roller. So it’s nothing like fine art, but that was the Grammy set of pieces. Like when you would see an act, those are the kinds of things they would make. And that survives somehow all the way to me finding it at Kirk Albert collectibles down in Georgetown.

Speaker4:

And can you describe a little bit more what it looked like?

Tom:

It’s just gray and all the features that you could tell that it was Bob Dylan were in a black paint, he’s smoking a cigarette and to me, it was so obvious right away. Some people don’t see it, but that’s how that happened. And we ended up with Marshall Amp speakers and we ended up with 1960s’ videos playing on the wall and the whole restaurant became kind of that 1968 flower power. And I had the whole installation of gerbera daisies in glass vases, kind of representing that. I just built from there. You never know when you’re going to get an inspiration, you might be walking through an art gallery and the painting talks to you in a way that just says I’m an opener diner. I don’t know what it is. I mean, those days are probably passed for me from the style of going about opening new restaurants in that way.

Tom:

But the idea of why this restaurant happened, it’s a flicker. And then all of a sudden it starts to build, it’s walking through a market in Spain on the Ramblas and saying, Jesus, we could do this. This is so good. It’s so fun. Well, let’s try something like this. And then my natural inclination is to start trying to be more authentic about the way it looks and the way it feels. And I try not to do it unless I have a real story around it. Like for example, Lola, to me, the story is Jackie’s Greekness, and Jackie’s grandfather. I feel good about that. I’ve never called it a Greek restaurant. I called it a Greek spirited restaurant. It’s what I would think of as what I would do now in a modern Athens restaurant. Never tried to say I was Greek. Nothing like that. And that’s the way I look at all my places, their inspirations, and not necessarily anything more than that.

Speaker4:

You have a very successful career, and it’s all centered here in Seattle. Is there a reason behind that? Why stay in one place and cultivated there?

Tom:

Well, I don’t know if you’ve met her, but I only have one daughter Loretta who’s about ready to have a baby boy named Hercules on the 4th of March. Theycan’t land on a name. So I named it for them. [crosstalk 00:23:45] We did, we had two names with Sage or Loretta. Her middle name is Rhoda Faye after her grandmother’s name, the Grandma Dot was Rhoda Faye. So what was your question?

Speaker4:

Why Seattle?

Tom:

Oh, why Seattle? Oh, why stay here? I just never had much interest in being on the road. I had a lot of friends, my peers of that age group did all of that. Whether it was Marcus Samuelsson, Mario Batali, Todd English, Emre, Wolfgang, you name all these people, they all did the national restaurant thing. And I never saw a whole lot of happiness there. I just saw people doing something like they felt like they needed to do.

Tom:

And I almost feel the same way about me. It felt right to keep expanding. Didn’t necessarily have to be that way. I’m a ADD. I don’t know what I am, but I just kept building. And for us, the inspiration had to go with having the money to do it. We didn’t borrow money from banks. And so for us, it was always like, if we have enough money, let’s try it. Why not? I’m an entrepreneur that way.

Speaker4:

Yeah.

Tom:

I’m not scared of risk. And in the restaurant business, you have a lot of risk.

Gina:

Hey, do you have a special memory from eating at a Tom Douglas restaurant? Head to Seattle Design Centers Instagram posts for this episode and tell us all the details. Inspired Design is brought to you by the Seattle Design Center. The show is produced by Larj Media. You can find them at larjmedia.com. Special thanks to Meechie Suzuki, Lisa Willis and Kimmy Design for bringing this podcast to life. For more head to seattledesigncenter.com, where you can subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media. If you’re looking for inspiration, come check out the Seattle Design Center in Georgetown. We’re open Monday through Friday from 9a.m. to 5p.m.